LAST PAGE

LAST PAGE RETURN TO INDEX

RETURN TO INDEX

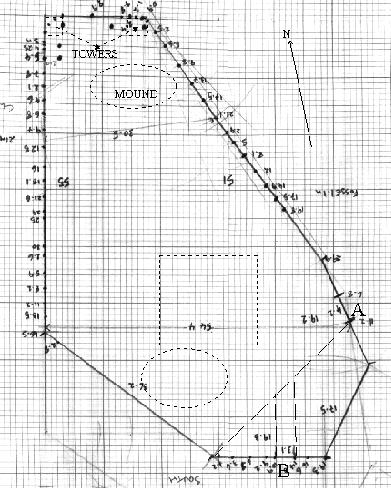

The Norman fort is seven sided, with two identifiable entrances (A and B) on the east and south sides. Overall the fort measures 77 meters in length, running on an axis north/south, with a width of 56 meters. Post holes have been located from dowsing at the points marked on the plan. This is currently part completed, due to the deadline for submission of material for the Department of Transport, and will be completed in due course.

The soil on the site is very thin at the southern end, with a blue/grey clay less than six inches from the surface. In consequence post holes can be located in some places, where the hole caused by a small wooden stake has been filled by organic debris. The stakes in question were small compared to what I, as a layman, would expect, being of various sizes from 1Ē to 1.5Ē in diameter. In many respects the same sort of support that would be expected for a relatively simple barricade. These stakes run completely round the site, at semi-regular intervals, and all are located on the top of a small mound, presumably caused by fill from the adjacent ditch.

At the northern end of the site there is an accumulation of sandy soil to a depth of between 80cm and 1meter where wind has moved the slope towards the sea. However this has been held back by some form of mound, covered with flat stones. These stones have an ironstone quality about them and appear to have been laid systematically in a large oblong circle. This oblong is app. 10 meters by 4 meters wide. The mound takes the appearance of a possible burial mound and in consequence I decided to make an experimental excavation. I needed to provide myself with evidence that this really was something worth pursuing, since all the research done so far was of an academic nature.

Could this mound be the same mound referred to by Poitiers and the Carmen? The mound where Harold was buried? or is it the mound where William buried his own men, referred to in Poitiers, neither of which has ever been identified.

The excavation in question was in the middle of a briar, in excess of 12 meters in diameter. Having cleared a reasonable area an excavation was started in the region of 2 meters long by one meter wide.

At a depth of 80 centimetres the sandy soil changed into a compact version of the same with the appearance of images in the soil. These were cleared with a small brush over a period of several weeks in the summer of 1993. The following pictures were taken to record the items uncovered. There were three items in all:

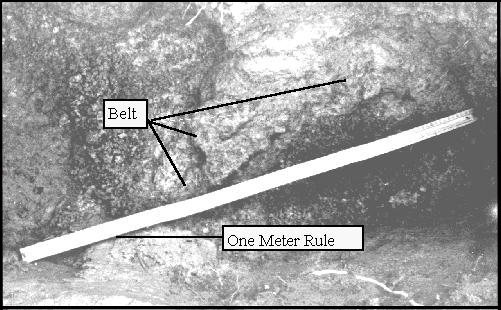

A belt type object was uncovered, shown immediately above the ruler. The age of the item was indicated as very old, since all recognisable magnetic imprint had been lost when examined under a metal detector.

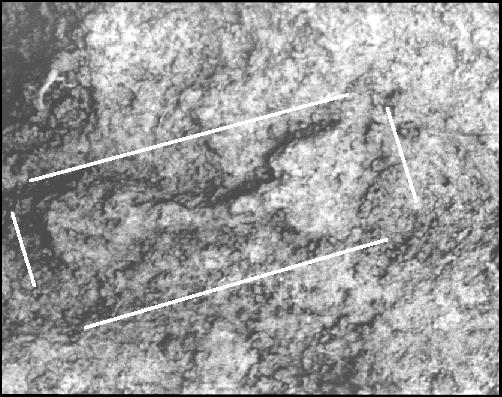

This item took on the well defined image of a possible axe head. It was rust coloured (more so than evident from the picture) and appeared solid metal.

The key type object was located at the eastern end of the excavation and rested upon something that could possibly have been organic in nature. To my untrained eye it appeared like leather but was solid in nature and not excavatable.

As a consequence of these observations I concluded that I was not qualified to take any further action and refilled the excavation with a view to getting professional help. What I am convinced about is that the mound in question is of great antiquity, having excavated many sites previous to this one looking for clues. It may relate to any of the periods that cover the history of this site, but it has particular interest in that the clues that led me there were hidden in documents which identify Haroldís burial at the Norman camp. If the site of the Norman camp is proven to be correct, this may be the site of the burial of the last Saxon King of England, exactly as portrayed by Wace, under a pile of stones on a headland overlooking the shore and the sea.

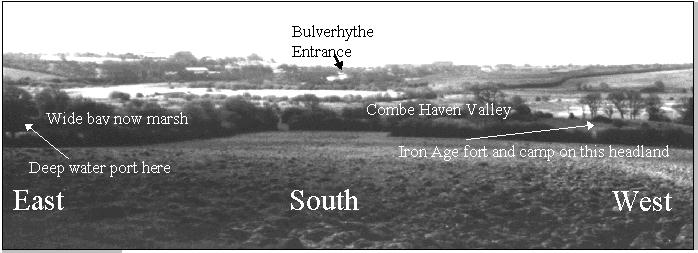

The western side of the fort runs along the top of the side of what was once a sea inlet, which opens on to the Bulverhythe. This inlet once had a cliff side to it, thus making any attack on this side impossible. The southern sides of the fort were also protected by the proximity of the sea and were connected to the Monkham Inlet by a man made track.

On the north and western sides there is a ditch, since this was the open front, from which any attack might be expected. The ditch is still in existence today, showing as a well defined indent, with earth piled behind where the palisade once stood. No excavation has yet been undertaken, since none was necessary to identify the feature.

The picture shows the ditch running from the top right (north) to the bottom left (south) behind the oak tree - known as the oak tree of Guienne. In the background behind the oak tree you can see the mound with briar still intact.

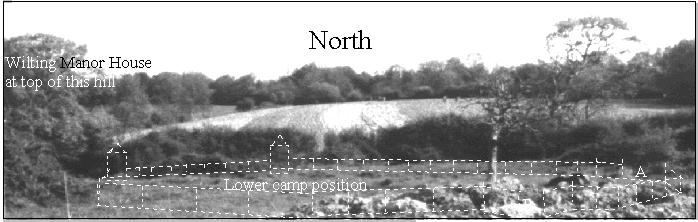

Another picture shows the position of the camp in relation to itís position on the edge of the Bulverhythe. The field in front is still ploughed in strips by the farmer . In times before mechanisation fields were ploughed by oxen. In consequence fields were ploughed in strips horizontally in order to avoid the need for the oxen to plough uphill.

The same view taken looking north shows the strips in the same way as the Bayeaux Tapestry (Plate 12) shows strips behind the fort.

At the main entrance on the eastern side of the fort (A), there is an entrance leading on to the main plain. The earth has been levelled out at this point and within the perimeter there are definite signs of partitioning into various sub-areas, by the use of earthen ditches with attendant mounds. In the centre is a raised circular area, also in common with the picture shown in the Bayeux Tapestry.

The position of the fort coincides exactly with the parameters set out in our summary (135) of documentary evidence I therefore decided that sufficient evidence now exists to warrant a full resistivity survey of the field in question, since it is important to establish whether any features are hidden in the soil which has been deposited there over the centuries. Certainly the fort did not appear to me as a traditional shape, but then I admit that I am not an expert on these matters. The dowsing that I had carried out confirmed two towers at one end, together with confirmation that this was the camp of William the Conqueror. I have deliberately understated the importance of dowsing in the search for this site, mainly because of the reluctance of serious academic minds to accept that dowsing works. Why it works and how it works is not a concern that I am interested in here. All I have to say on the matter is that having climbed over most of the fields in an area of several square miles around Hastings, over a period of many years, there is only one site that responds positively to dowsing that I have found. Many is the time that I have thought that I might have found the correct site, only to get a negative response to the dowsing technique. The fact that I could then support this location historically and with archaeological evidence raises many more questions than it may answer. Consequently I do not wish to address those issues here, but prefer to concentrate on the simple issue of what proof is in the ground. It is possible to argue for ever the merit of one case against another, but at the end of the day Pevensey must lose the argument about the landing site because it cannot argue against a Norman fort at the old port of Hastings. To do that would be to ignore the vast weight of historic record showing Hastings as the landing site.

It is for this reason that a resistivity study needed to be the next step, since this would reveal the existence, or otherwise, of any solid building structures, together with ditches or other features which produce differences in soil resistivity. The advantage of doing a resistivity study is that the underlying archaeological material could be revealed without destroying the site. At the same time the raw data can provide a good visual image of the underlying geology together with any human involvement when removed by computer filtering.